The DNA Network |

| What Medicine Owes the Beatles [Epidemix] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 06:59 PM CDT

Here’s the story: in the 1960s, a middle-aged engineer named Godfrey Hounsfield was working at Eletrical & Musical Instrument Ltd., where he began as a radar researcher in 1951. The company, known as EMI for short, was a typical industrial scientific company at the time, working on military technology and the burgeoning field of electronics. Hounsfield was a skilled but unexceptional scientist, leading a team that built the first all-transitor computer in 1958. Through its work in radar the company began working in broadcasting equipment, which complimented its ownership of several recording studios in London. Specifically, at Abbey Road. In the 50s, the company began releasing LPs, and by the end of that decade, thanks to an acquisition of Capitol Records, the company had become a powerhouse in popular music. Then, in 1962, on the recommendation of EMI recording engineer George Martin, the company signed the Beatles to a recording contract. That was the bang - over the next decade (and for years thereafter) the company earned millions of dollars from the fab four. So much money, the company almost didn’t know what to do with it. Meanwhile, Hounsfield’s success with computers had earned him good standing in the science side of the company. Flush with money broken out of teenagers’ piggy banks worldwide, EMI gave Hounsfield the freedom to pursue independent research. Hounsfield’s breakthrough was combining his work with computers together with an interest in X-rays. Invented in 1908, X-rays were still pretty much used to image bodies in two dimensions from a fixed position. Hounsfield’s idea was to measure in three dimensions, by scanning an object - most dramatically, a human head - from many directions. The result was a cross-sectional, interior image that he called computed tomography, or CT. As the Nobel Prize committee put it, in giving him the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1979, before the CT scanner, ”ordinary X-ray examinations of the head had shown the skull bones, but the brain had remained a gray, undifferentiated fog. Now, suddenly, the fog had cleared.” First released as a prototype by EMI in 1971 - the year after the Beatles broke up – CT scanners started to appear at hospitals in the mid 1970s; today there are about 30,000 in use worldwide. Just a bit of trivia, apropos of nothing. A historical take from somebody who worked with Hounsfield is here. Hounsfield’s Nobel lecture is here. |

| How do we educate physicians? [The Gene Sherpa: Personalized Medicine and You] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 02:41 PM CDT |

| Laboratory Science: From Penal Colonies to Video Game Arcades [The Personal Genome] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 02:33 PM CDT Laboratory science is filled with dull, repetitive tasks. Casting gels, pipetting, streaking plates, and on and on. Did you know adult C. elegan worms have 969 cells? Well they do. We know that because a number of graduate students It should come as no surprise that laboratories have been compared to penal colonies. Glorified work camps for the technically adept! The root word of laboratory is “labor” after all. Does the practice of science really need to be this way? Could science and laboratory work be more playful? In Shapiro’s 1991 book, The Human Blueprint, George Church wonders whether the lab could be turned into something more akin to a video game arcade:

Comparisons of science careers to video games are much more fun than comparisons to labor camps or penal colonies. The quote from George above challenges us to think beyond metaphors. How might the laboratory environment itself be transformed into something more playful, fun, and engaging? – Robert Shapiro, The Human Blueprint. St. Martin’s Press, 1991. [quote from page 252] |

| New Educational Model For A New Century [Genomicron] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 01:14 PM CDT Over at the home of Genomicron 2.0 (ScientificBlogging.com), physicist, education expert, and Nobel laureate Carl Wieman has an important post about 21st century post-secondary science education. Optimizing The University - Why We Need a New Educational Model For A New Century

|

| Genes Influence Antidepressant Effectiveness [A Forum for Improving Drug Safety] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 11:18 AM CDT Variations in the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 directly affect how patients respond to citalopram according to a Mayo Clinic Study just released in the current issue of the American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. Researchers examined the serotonin transporter gene, or SLC6A4, in 1,914 study participants. The study showed that two variations in this gene have a direct bearing on how individuals might respond to citalopram. SLC6A4 produces a protein that plays an important role in achieving an antidepressant response. In this study, researchers evaluated the influence of variations in SLC6A4 in response to citalopram treatment in white, black and Hispanic patients. Researchers found that white patients with two distinct gene variations were more likely to experience remission of symptoms associated with major depression. No associations between the two variations and remission were found in black or Hispanic patients. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, antidepressants are the most prescribed medication in the country, but many stop taking their medication early because of negative side effects or lack of response. Pharamcogenetic testing looks at genetic variations like SLC6A4 that affect response so medications can be personalized for the patients to help avoid these treatment failures and side effects. Dr. Mrazek, director of the Genomic Expression and Neuropsychiatric Evaluation (GENE) Unit at Mayo Clinic, stated "first, we started with trial and error - which feels like flipping a coin to select a medication. The Holy Grail would be to be able to consider the implications of variations in many genes. Ultimately, we hope to be able to determine with great accuracy which patients will respond to specific antidepressants and which patients will almost certainly not respond."  |

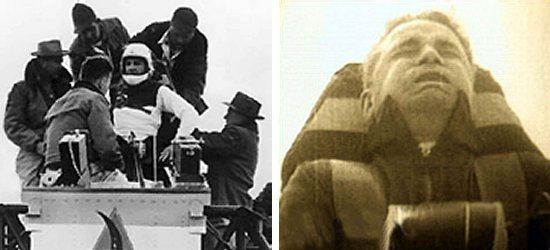

| Badass Scientist of the Week [Bayblab] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 11:03 AM CDT  As with last week's badass scientist of the week, this week's scientist is both a thinker, and a human guinea pig. I present to you, John Paul Stapp - Colonel with the USAF, and fastest man on earth. Dr Stapp was born in Bahia, Brazil, and joined the USAF just around the end of WWII. He was posted to the Aero Medical Laboratory, where he was placed in a team looking at oxygen delivery at high altitudes, as well as the prevention of the bends as the pilot changes pressures frequently. That work lead to a number of currently used techniques. He was then moved to the deceleration project in 1947 - where he was looking at deceleration from high speeds using the 'gee whizz' rocket (4-kN acceleration) propelled simulator. One of the earlier innovations to come from this set-up was the safety of having rear-facing seats, which are installed in all USAF transport aircraft. The wider scientific community believed the human body could not survive more than 18 Gs of deceleration--Stapp hit 35. In 1954 he decelerated from 120 miles per hour to 0 in a little under one-and-a-half seconds, and received two huge black eyes as a payoff. Apparently, he was blinded for two days as an added bonus. By some accounts, and he also broke his back, arm, wrist, lost six fillings and the icing on the cake? He got a hernia, and apparently had his retinas pop off more than once. In return for these injuries, he then built a bigger rocket, believing that the limits of human deceleration had not been fully tested (what did he think was going to happen at the end of those limits?!), and eventually reached a peak G-force of about 42.6 Gs. He pioneered work in Murphy's law (named after Major Edward Murphy, an Engineer on the team). He also flew about in a jet aircraft (at 917 Kph) without a canopy to establish that the wind effects at those speeds would not harm a person. Fortunately, he was right on that one. |

| On the origins of clapping [Bayblab] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 10:43 AM CDT  This question has been on my mind for a while. I always get chills when I'm in a large group clapping. I find it such a strange behaviour. Whether I clap or not cannot be heard by the performers, because all they hear is the thunderous applause of the group, but I feel compelled to do so. Yet when you add everything up, the loudness gives the performers an indication of how much enjoyment they've provided to the group as a whole. The other thing I find funny is that we do not clap in synchrony: it is totally chaotic. Everyone has their own clapping rhythm, which I assume may change depending on the mood but probably falls within a personal bell curve. The other thing I wonder is who started this tradition. I've seen it in every ethnic group I have encountered while traveling, even remote tribes in the jungle with very little outside contacts. I seems as universal as music. And I suspect it shares common origins, which probably were invented independently multiple times. I have heard that even babies seem to inherently want to clap, in which case it might not need to be invented and could be an innate behavior. However clapping can be substituted with feet stumping, but the idea is the same, a loud noise, with a constant rythm. So does clapping precede music, are they even related? Why the hell do we do it? This question has been on my mind for a while. I always get chills when I'm in a large group clapping. I find it such a strange behaviour. Whether I clap or not cannot be heard by the performers, because all they hear is the thunderous applause of the group, but I feel compelled to do so. Yet when you add everything up, the loudness gives the performers an indication of how much enjoyment they've provided to the group as a whole. The other thing I find funny is that we do not clap in synchrony: it is totally chaotic. Everyone has their own clapping rhythm, which I assume may change depending on the mood but probably falls within a personal bell curve. The other thing I wonder is who started this tradition. I've seen it in every ethnic group I have encountered while traveling, even remote tribes in the jungle with very little outside contacts. I seems as universal as music. And I suspect it shares common origins, which probably were invented independently multiple times. I have heard that even babies seem to inherently want to clap, in which case it might not need to be invented and could be an innate behavior. However clapping can be substituted with feet stumping, but the idea is the same, a loud noise, with a constant rythm. So does clapping precede music, are they even related? Why the hell do we do it?Does anybody out there know of a good explanation or theory on the origins of clapping? |

| Posted: 16 Jul 2008 10:18 AM CDT Carl Zimmer has posted a spiffy summary of the word usage in his book Microcosm using the super cool Wordle site. For fun, I put in the text of two recent papers (one in press, one in review). I guess you can kinda see what they are about.

|

| The Woodstock of Evolutionary Biology and eye rolling [Genomicron] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 10:16 AM CDT In a recent issue of Science there was a piece by Elizabeth Pennisi on the "Altenberg 16" who will be attending what overhyping journalist Suzan Mazur calls the "Woodstock of Evolutionary Biology", only it "promises to be far more transforming for the world". Puh-lease. People have been saying that the Modern Synthesis is neither modern nor a synthesis and needs to be expanded for some time. And there are a lot more than 16 people saying it. Thankfully, Pennisi uses the nonsensical hype to discuss some relevant issues, and even points out that the people involved themselves do not see it as a revolution.

My eyes have rolled -- and did so again at the sight of this latest report, until I saw that it was much more reasonable.

I look forward to reading the papers that emerge from the meeting, but I don't expect anything revolutionary -- more like some cool ideas to continue discussing.

|

| Did Darwin delay? [Genomicron] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 10:14 AM CDT In my evolution course, I note that "Darwin spent 20 years working out his ideas and gathering evidence" before releasing On the Origin of Species in 1859. I don't say he "delayed" publication purposely, though in many cases this long period from idea to outcome has been attributed to fear of the reaction from the clergy, colleagues, society at large, his wife, etc. On this issue, a few bloggers have pointed to a recent essay by John van Wyhe (2007), in which it is argued that there was no delay based on fear, only a protracted writing period. Other historians do not necessarily agree, though the blogs I saw did not mention this. As Odling-Smee (2007) says,

I think "yes or no" to the question of whether Darwin delayed publication out of fear is very simplistic. Anyone who has written anything of substance knows that sometimes the effect of fear of reaction is procrastination and/or excessive desire to include every piece of information available. Both can cause writing to take longer than it otherwise would. Was Darwin thorough? Yes. Is that one reason it took so long? Undoubtedly. Was he so thorough because of a fear of reaction? Probably at least in part. _______ Odling-Smee, L. 2007. Darwin and the 20-year publication gap. Nature 446: 478-479. Van Wyhe, J. 2007. Mind the gap: did Darwin avoid publishing his theory for many years? Notes and Records of the Royal Society 61: 177-205.

|

| A few more quotes about non-coding DNA. [Genomicron] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 10:12 AM CDT Just for fun, here are some quotes I came across while reading a few sources for a paper I am writing. Remember, a significant number of creationists, science writers, and molecular biologists want us to believe that non-coding DNA was totally ignored after the term "junk DNA" was published in 1972, that the authors of the "junk DNA" and "selfish DNA" papers denied any possible functions for non-coding elements, and, in the case of creationists, that "Darwinism" is to blame for this oversight. The latter of these is nonsensical as the very ideas of "junk DNA" and "selfish DNA" were postulated as antidotes to excessive adaptationist expectations based on too strong a focus on Darwinian natural selection at the organism level. For those of you who didn't read the earlier series, see if you can guess when these statements were made.

(E) (F) Answers to be provided in the comments.

|

| No such thing as natural selection? [Genomicron] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 10:05 AM CDT In reading an interesting article in the New York Times (in part because it quotes my colleague Andrew MacDougall), I came upon this statement that caused a bit of a cough.

Yes, humans have some impact on a great portion of the globe, but this is nonsense for at least three reasons. One, just because humans are involved does not make something "artificial selection" and therefore disqualify it as natural selection, even within the formulation of Darwin and Wallace which drew a distinction . Artificial selection is the intentional breeding of organisms on the basis of some characteristic (e.g., sleek body shape in dogs or high yield in crops). If we dump waste in the ocean and this creates new selective pressures on marine animals, this hardly counts as artificial selection. From the point of view of the organisms involved, it is simply a change in the environment, and natural selection will then operate as usual. (As a matter of fact, I don't consider "artificial" and "natural" selection to be fundamentally distinct processes anyhow -- feel free to discuss in the comment section). Two, we may influence environments generally, but there are, as we speak, gazillions of organisms out there struggling for survival and hunting, parasitising, avoiding, mating with, and otherwise interacting with one another independent of human action. Three, natural selection is still occurring both in human populations and indeed within human bodies (among pathogenic agents, for example). (Hat tip: John Hawks blog)

|

| Stephen Hawking moving to Canada? [Bayblab] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 09:48 AM CDT Apparently Hawking is disgruntled with the current science funding cuts in place in Britain and may leave Cambridge to join the famous Perimeter Institute! If you don't know about the perimeter institute it's a Waterloo-based theoretical physics institution founded/funded by the RIM (of blackberry fame) maverick Mike Lazaridis, and it is known for its collegial atmosphere and high profile members. This is quite a coup. No word yet if he'll be back on the bayblab podcast... |

| Science career as a video game? [The Daily Transcript] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 08:41 AM CDT Inspired by a conversation with Awesome Mike. Your science career, what type of video game is it? At times it might resemble a labyrinth full of demons that you must slay. (Or maybe it's like Grand Theft Auto? Well since I've never played that game nor Halo, I'll stick to the metaphorical game that's running through my head.) Level 1: Undergraduate The first level is the easiest. Stay focused and you'll get to the end. Final monster at the end of the round? Those exam finals? Psht. Level 2: Grad Student This level bit trickier then the previous one. The first major obstacle is choosing the right lab. Pick a postdoc laden lab full of premadonas and you may end up loosing many bonus lives unnecessarily to all sorts of nasty creatures hiding in each corner. Pick a lab where the work is interesting and where you'll receive a good training and you may gain valuable extra powers that can be useful in higher levels. The last dragon to slay in this level is the thesis. In many ways this is the hardest part of this level but in no way near the most challenging. Level 3: Postdoctoral fellow In comparison to the previous level, the choice of lab is even more critical. You want a good environment with good connections that has a history of postdocs moving on to the next level. You also want to have a project that you can bring with you. The final dragon to slay at the end of the round? Surviving the eighteen headed monster that is the job market for academia. Unlike in the previous level this monster is brutal. But if you've laid down the proper ground work and have an interesting (and findable) research plan, you'll slay this monster (hopefully). I am in the process of slaying the multi headed dragon. (Yes this post is a hint as to what's been happening in my science life besides travelling across Europe). But level 3 is as far as I've reached in this game. You can fill me in as to what is to come in the next. But I can imagine ... Level 4: Assistant Professor, Level 5: Full Professor and Level 6 ... Grand Poobah? Read the comments on this post... |

| Cool New Blog Carnival [Bayblab] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 08:35 AM CDT The Giant's Shoulders is a brand new blog carnival focusing on the history of science. Bloggers are asked to write posts about classic papers or profiling important people or concepts. Contributors should not only describe the research involved but also put it in a broader historical/scientific context: why is the work in question important/groundbreaking/revolutionary/nifty? [...] Entries profiling an important person or concept in the history of science are also acceptable.The inaugural edition has gone up at A Blog Around the Clock and it's a doozy - dozens of entries profiling work as far back as 1543 and covering diverse areas from medical case studies to classic physics to ... Dungeons and Dragons? Check it out. |

| Personalized Medicine in Video [ScienceRoll] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 05:13 AM CDT Deanna Kroetz of UCSF’s School of Pharmacy talks about the promise and the limitations of personalized medicine. (Hat tip: Medical Quack) Further reading:  |

| Unnatural Approach to Diabetes [Sciencebase Science Blog] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 04:15 AM CDT

But some offer quite convincing claims for treating, but not necessarily curing, a specific illness with something novel. One such email arrived recently from a public relations company representing a company selling a herbal supplement. The release discusses the potential of an extract of mulberry leaf to prevent concentration spikes in the blood sugar of patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. This disorder, which is on the increase in the developed world as obesity incidence rises, is characterised by insulin resistance, relative insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia (raised blood sugar levels). Changes in diet and more exercise can often ameliorate the effects in the early stages, but medication and insulin are usually needed in the long term. The main problem is the sharp rises and falls in the concentration of glucose in the blood, which puts a severe strain on the organs, in particular the heart. The email I received, had the subject line “Type 2 diabetes: a look at natural alternatives to prescription drugs” and seemed innocuous enough. It mentioned the FDA’s pronouncements on diabetes drugs and the need to tighten up on their safety and then went on to highlight mulberry, a natural product that is now being marketed as Glucocil, which can purportedly help prevent those hazardous blood sugar spikes. According to the press release, mulberry has been used for generations in Chinese medicine and some Indian foods, is showing great promise for Type 2 diabetes sufferers. After seven years of research and development, a medical researcher and scientist from China, Lee Zhong, has discovered a proprietary mulberry leaf extract that has been shown in numerous clinical trials to markedly lower blood sugar levels in Type 2 diabetics, helping them achieve a healthier diet and lifestyle. I asked Zhong for a few details about his work, the efficacy of this food supplement and possible medical issues associated with its use. You can read more about the study in the latest issue of Reactive Reports. Zhong explains that, “Mulberry leaf It all sounds reasonable so far. But, what is not clearly mentioned in the press release is that Glucocil is not simply mulberry extract. Rather it is a blend of different ingredients:

I asked Zhong about the presence of that chromium salt, as chromium deficiency has long been suggested to be a factor in the development of diabetes. “Chromium was not included in the extracts that used in our published clinical studies (or the efficacy tests),” he told me, “The ingredients used in the final Glucocil formula have records of many years’ safe human usage.” He adds that, “Glucocil was not developed overnight. We had thousands of tests and have plenty scientific evidence to support the product.” That’s as maybe, but, I think he missed my point, it’s not the safety of the formulation that concerns me, although chromium picolinate has been linked to liver toxicity (Eur J Intern Med. 2002, 13, 518-520), it’s how it can be marketed as a natural product when it so obviously contains a rather non-natural ingredient in the form of that chromium salt. It seems especially odd given that chromium itself is thought to have an effect on diabetes, although that’s as yet unproven. Aside from the clinical trials and tests carried out with mulberry in isolation, as far as I know, no double-blind placebo-controlled trials have been carried out on the mixed formulation that includes the chromium salt, which has variously been used as a “natural” slimming aid without serious proof of efficacy. Chris Leonard, Director, Translational Research and Technology at Memory Pharmaceuticals, points Sciencebase readers to what he describes as a “thoughtful and well-referenced discussion on chromium and diabetes. Pharmacologist and toxicologist Sanjeev Thohan, Research Director at drug discovery company Exelixis, adds that chromium picolinate is quite distinct from the hexavalent form of chromium made infamous by the Erin Brokovich issue. He points out that there have been some clinical trials conducted within the last year that use different derivatives of chromium picolinate and that these are close to finishing and will make their data available in the next year or two. He adds that one must, “Remember that the bioavailability of the picolinate derivative and its action on the beta cells is what will determine if there is a positive effect on insulin. Insulin sensitizer drugs, I believe in some of the clinical trials, are being used with the chromium compounds to see the possibility of synergy.” Thohan highlights an additional UK government PDF resource on chromium. The US government’s PDF document on dietary recommendations for vitamins and trace elements also includes a section on chromium. Zhong adds that, “This product is being marketed as a dietary supplement (not a food or drug) and is designed to assist those who are trying to manage their condition primarily through changes in lifestyle, primarily diet and exercise.” But, to my mind, something with proven activity in such a potentially debilitating disease should not be marketed as a supplement. Consumers should be made aware of the dangers of diabetes and consult their doctor over possible treatments and outcomes. Zhong tells me that the marketing does stress that potential users talk to their healthcare workers and that they should monitor their blood sugar carefully. However, one in ten, he concedes, don’t necessarily do so. With diabetes on the rise, one in ten could turn out to be quite large numbers of people using an apparently potent supplement without any clear knowledge of what it might be doing to their bodies and without strictly monitoring the progression of their disease. “Generally speaking, those who are most interested in this product are those who are newly diagnosed and are not on multiple meds as is the case with those who are more seriously ill,” adds Zhong, “The typical Glucocil consumer is someone who is looking for more natural nutritional support.” Yes, there are problems with pharmaceutical products. But, maybe its time physiologically active herbal remedies were

A post from David Bradley Science Writer Unnatural Approach to Diabetes |

| What does DNA mean to you? #14 [Eye on DNA] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 03:04 AM CDT

|

| Dreaming of a life science Semantic Web platform [business|bytes|genes|molecules] Posted: 16 Jul 2008 12:01 AM CDT I have long been intrigued by IO Informatics and their flagship Sentient Suite. Bio-IT World is carrying an article about the company that reminded me of that interest. I have never used it, so I wonder if anyone else out there has? Now the Sentient Suite doesn’t really sit on the WWW, so it’s not really an optimal Semantic Web product, but it does use RDF, a wonderful data model for the kind of data life scientists use, rich in relationships and metadata, and SPARQL to query the data. So at least within the confines of a company’s data sources, in theory you have a rich graph of data which can be queried. I’ve long felt that we either don’t leverage structured data optimally in much life science software, or over engineer it. The company claims to be smart about how it’s doing this, although given the complexity of data, how well they achieve their goals is something I question. My ideal would be a life science version of the Talis platform, perhaps with an industry facing side (much the way Talis has its library business), and a public facing side that sits on the web with published APIs and the underlying technology that allows developers to build tools on top of it. I am sure they’d be a ton of takers. IO has one side of this (the enterprise facing side). Would be cool if they, or someone else, made a platform available publicly, with some underlying intelligence that can be leveraged by APIs. |

| Conflict of interest and openness [The Tree of Life] Posted: 15 Jul 2008 11:00 PM CDT The New York Times had a long and extensive article on conflicts of interest in medicine. See Times article here. I was pleasantly surprised to see them discuss the concept that open access to data can help correct for bias if it occurs by allowing others to redo analyses. For example: "Having everyone stand up like a Boy Scout and make a pledge isn't going to quell suspicion," said Dr. Donald Klein, an emeritus professor at Columbia, who has consulted with drug makers himself. "The only hope to rule out bias is to have open access to all data that's produced in studies and know that there are people checking it" who are not on that company's payroll.Unfortunately the Times does not raise the issue of access to the publications themselves. Clearly having the data is good. But if nobody can read the papers and they can just read the press releases that come from the papers, we are all doomed. |

| There's a Whole Doubt Industry Aimed At Science [adaptivecomplexity's column] Posted: 15 Jul 2008 10:03 PM CDT "Can scientists and journalists learn to beat the doubt industry before our most serious problems beat us all?" This is the question asked in an interesting piece at a news? site I've never heard of - "Miller-McCune: Turning Research Into Solutions." I'm not sure about the research and solutions thing, but they do have some interesting comments about the "Doubt Industy." "Doubt Industry" means organized interests with a strong motivation to get the public to question science: the link between smoking and cancer, the scientific status of evolution, the health hazards of beryllium (apparently a problem for workers in the atomic industry). Whenever scientific results cause problems for someone, especially someone with a strong financial incentive to not believe the science, the time-tested strategy is to question the certainty of the science. A well-known internal memo from one cigarette company in the 1960's famously claimed(PDF): |

| If life begins at conception, when does life start & when does it end? [Omics! Omics!] Posted: 15 Jul 2008 09:30 PM CDT Yesterday's Globe carried an item that Colorado is considering adopting a measure which would define a legal human life as beginning at conception. Questions around reproductive ethics and law raise strong emotions, and I won't attempt to argue either one of them. However, law & ethics should be decided in the context of the correct scientific framework, and that is what I think is too often insufficiently explored. Defining when life "begins" is often presented as a simple matter by those who are proponents of "life begins at conception" definition. However, to a biologist the definition of conception is not so simple. Conception involves a series of events -- at one end of these events are two haploid cells and at the other is a mitotic division of a diploid cell. In between a number of steps occur. The question is not mere semantics. Many observers have commented that a number of contraceptive measures, such as IUDs and the "morning after" pill would clearly be illegal under such a statute, as they work at least in part by preventing the implantation of a fertilized egg into the uterine wall. Anyone attempting to develop new female contraceptives might view the molecular events surrounding conception as opportunities for new pharmaceutical contraceptives. For example, a compound might prevent the sperm from homing with the egg, binding to the surface, entering the egg, discharging its chromosomes, locking out other sperm from binding, or prevent the pairing of the paternal chromosomes with maternal ones (there's probably more events; it's been a while since I read an overview). Which are no longer legal approaches under the Colorado proposal? At the other end, if we define human life by a particular pairing of chromosomes and metabolic activity, then when does life end? Most current definitions are typically based on brain or heart activity -- neither of which is present in a fertilized zygote. Again, the question is not academic. One question to resolve is when it is permissible to terminate a pregnancy which is clearly stillborn. Rarer, but even more of a challenge for such a definition, are events such as hydatiform moles and "absorbed twins". In a hydatiform mole an conception results in abnormal development; the chromosome complement (karyotype) of these tissues is often grossly abnormal. Such tissues are often largely amorphous, but sometimes recognizable bits of tissue (such as hair or even teeth) can be found. Absorbed twins are the unusual, but real, phenomenon of one individual carrying a remnant of a twin within their body. Both of these conditions are rare (though according to Wikipedia in some parts of the world 1% of pregnancies are hydatiform moles!) but can be serious medical issues for the individual carrying the mole or absorbed twin. Are any these questions easy to answer? No, of course not. But they need to be considered. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The DNA Network To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email Delivery powered by FeedBurner |

| Inbox too full? | |

| If you prefer to unsubscribe via postal mail, write to: The DNA Network, c/o FeedBurner, 20 W Kinzie, 9th Floor, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

As regular readers will be aware, I’m very

As regular readers will be aware, I’m very

No comments:

Post a Comment