The DNA Network |

| Yet another online site for scientific networking [The Daily Transcript] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 03:54 PM CDT I've sign into yet another sciency LinkedIn type site. This time it's Epernicus. I've had a good look at the site, it's about on par with SciLink with some exceptions. 1) The scientific genealogy application on SciLink is much better then that on the Epernicus site. Why? You can extensively modify the tree beyond your own personal connections. Bigger trees are better (more info). 2) The profile page of Epernicus lists all your publications in chronological order - SciLink take note. So by my quick score it's 1-1. I guess like every other epic battle (VHS vs. Beta, HD DVD vs. blu-ray and AC vs. DC) the winner will soon be acclaimed by popular demand. Read the comments on this post... |

| Word of the week: Valsalva maneuver [Bayblab] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 12:43 PM CDT Named after the famed Italian anatomist of the 17th-18th century, the Valsalva maneuver entails forcibly exhaling against a closed glottis. This is typically used to open the Eustachian tube and equalize inner ear when experiencing a change of pressure (like during diving). Additionally, I had to explain to my students that it is also a method to facilitate defecation. Consider yourself warned, next time you're landing on a plane... |

| Posted: 18 Jul 2008 12:09 PM CDT (Re-posted from Genomicron 2.0) In one of my snarkier moments, I coined the term "Dog's Ass Plot" (DAP) in reference to

This was based on a figure that purported to demonstrate a relationship between non-coding DNA and complexity.

As I noted,

Now, GraphJam has posted a figure that is not only a superb DAP (i.e., the presentation implies a pattern that extends beyond the data themselves), but a Human's Ass Plot, or a HAP DAP:

|

| What's wrong with these figures? (Poaching content from Evolgen edition). [Genomicron] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 12:03 PM CDT I already posted one of these figures from reports on the platypus genome over at Genomicron 2.0 in an earlier round of What's wrong with these figures?, but the other one of them I hadn't noticed. For the answers, please see the post on Evolgen.   |

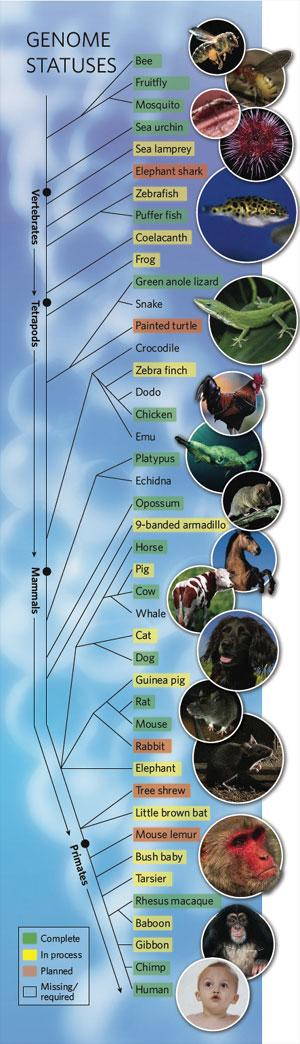

| The Great Chain of Phylogenetic Wrongness [evolgen] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 12:00 PM CDT Phylogeny Friday -- 18 July 2008 When they published the initial analysis of the complete platypus genome (doi:10.1038/nature06936), Nature, as they're wont to do, also put out a news item announcing the major findings (doi:10.1038/453138a). That news article included a phylogeny illustrating the evolutionary relationships of various animal species in various stages of having their complete genomes sequenced. The problem with the illustration: they got some of the relationships wrong. This sparked a letter from Peter Ducey of SUNY Cortland (doi:10.1038/454027d), in which he wrote the following:

In all honesty, the tree is so craptacularly drawn that it's hard to say that Archosaurs and Mammals are monophyletic based on the illustration. It looks more like the branching order of most vertebrates (and most animals) is unresolved, but I can definitely understand how Ducey interprets the tree. Either way, Nature did a bad job with this illustration. Why did they suck so bad? Here's what Ducey thinks:

Totally! The idea of a great chain of being, starting with bacteria and progressing through animals to humans, permeates much of the popular discussion of evolution. And it's just not true. It's a phylogenetic fallacy. Coincidentally, Ducey points out, Science repeated the same error Nature made. In their coverage of the platypus genome paper (doi:10.1126/science.320.5877.730), Science included this image:

Ouch! At least the tree accompanying the Nature article was ambiguous enough that it could be interpreted to represent the true phylogeny. While the cladogram from Science does not perpetuate the great chain of being myth, it does represent a completely resolved phylogeny that also happens to be incorrect. Read the comments on this post... |

| Which baby do you want? A dilemma for the 21st century parent-to-be [Genetic Future] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 10:37 AM CDT  Nature News has an intriguing article on the next three decades of reproductive medicine: essentially a series of short musings from scientists working in the field about the issues we will be facing in 30 year's time. It's worth reading through in full, but this statement from Susannah Baruch at Johns Hopkins caught my eye: There's speculation that people will have designer babies, but I don't think the data are there to support that. The spectre of people wanting the perfect child is based on a false premise. No single gene predicts blondness or thinness or height or whatever the 'perfect baby' looks like. You might find genetic contributors but there are so many environmental factors too.I'm unsure how selecting amongst these embryos doesn't count as making "designer babies" (it's still a choice, even if it's between a set of imperfect options), but I think Baruch's second paragraph is spot-on. It's clear from recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for height and weight that many (if not most) traits are hideously complex at the genetic level - a mess of common and rare genetic variants scattered throughout the genome, each contributing only the tiniest proportion of the overall variation. Height is a great example: GWAS results from more than 30,000 individuals have uncovered dozens of contributing variants, which together predict less than 5% of the variation in height. There's no doubt we'll uncover much of the remaining variation with emerging technologies (analysis of structural variation, and large-scale sequencing) and larger cohorts, by which time we'll likely have hundreds of contributing variants. The same will hold more or less true for other complex traits, including susceptibility to common diseases like diabetes or hypertension. The point is not that we will never understand the genetic basis of complex traits - we will, at least to a pretty good approximation, given advanced tools and sufficiently large cohorts. The point is that even once we understand the genetics of complex traits perfectly, that won't be enough to generate a "perfect baby" through embryo screening alone. To illustrate this, imagine - ten or fifteen years from now - a couple who have just had IVF to generate perhaps two dozen embryos, and want to use genetic testing to decide which one(s) to implant. There won't be a single, stand-out embryo, perfect and disease-free, because generating a "perfect" embryo - one with the "desirable" variant at every single position in the genome - runs up against a pretty serious probabilistic challenge. Let's say there are only 5,000 DNA variants that negatively affected human health (an under-estimate) each with a frequency of just 1%: that means you would get a "perfect" embryo around once in every 1022 attempts (that's a 1 followed by 22 zeroes, a stupidly large number). It's likely that methods to generate large numbers of embryos will be developed, particularly once stem cell technology enables sperm and egg cells to be created from adult tissue, but generating and screening 1022 embryos is no mean feat: at the rate of one every second, this would take you about 200,000,000,000,000 years, ten thousand times longer than the current age of the universe. So it's safe to say that there will be no perfect baby. Instead, the prospective parents will face a tough choice between embryo A, who will likely be tall, slim, smart and cancer-free but have a higher-than-average chance of bipolar, early-onset dementia, and infertility; embryo B, who will be a little shorter, dark-haired, probably fairly gregarious, resistant to coronary artery disease, susceptible to bowel cancer, hypertension and early deafness; embryo C, who will be of average intelligence, unlikely to suffer premature baldness, prone to mild obesity and diabetes, but not at a high risk of any of the other major common diseases; and embryos D-N, who present a similar panel of competing probabilities. The parents-to-be will sit down together with dossiers listing a huge set of statistical predictions for each of their potential children, and make a decision as to which (if any) of these abstract collections of traits and risks they wish to bring into this world. Decisions don't get much more emotionally traumatic than this: not only will they be making a decision that will shape their own lives and that of their future offspring, parents will carry a new, extra burden of responsibility for the fate of their children. If they decide on embryo A, and their child goes on to develop severe bipolar disease, they will carry the guilt of that decision in addition to the trauma of the disease itself. That's not to say that embryo selection is unworkable - in fact, I think it's inevitable - but rather that this process is likely to require a degree of agonising trade-offs on the part of parents-to-be that is seldom fully appreciated. While I have no moral problem with the notion of embryo selection, part of me is glad that my child-bearing years are likely to be over before I have the chance to face this particular dilemma... |

| The impact of online publishing [The Seven Stones] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 10:32 AM CDT "I haven't browsed a table of content in ages; I find all my papers by Pubmed searches anyway". We have probably all heard this remark, which reflects a general trend as how online publishing has changed the way we retrieve scientific publications. In a study published today in Science, Evans ("Electronic Publication and the Narrowing of Science and Scholarship", Evans, 2008) presents data on citations patterns showing that the appearance of electronic publications has been accompanied by a decrease in the number of citations and a progressive restriction of citations to recent papers:

The interpretation offered is that online availability has driven citations to become more focused while less relevant articles are more easily filtered out. In addition, Evans argues that facile navigation through the network of hyperlinked citations may amplify the tendency to be influenced by other's choice when citing "reference" studies and thus accentuates the dominance of a restricted number of articles:

It is probably difficult to be sure that all sources of bias and confounding factors can be eliminated in this type of analysis. For example, on the Friendfeed discussion thread, LJ Jensen asks whether the sheer amount of published research could explain why scientist restrict their citation to the most recent literature. See also some additional discussion in the associated News & Views (Couzin, 2008)

In any case, the study highlights two complementary strategies in information retrieval: finding relevant papers by targeted searches versus staying informed on a broad range of topics by systematic browsing. In our Google-driven era, we may have the tendency to forget the importance of good old-fashioned 'table-of-content-skimming' to stimulated cross-disciplinary thinking, widen our horizon and cultivate scientific curiosity. Perhaps it is a specificity of printed media to provide "poor indexing" and therefore enforce broad exposure to unrelated areas of research. On the other hand, some web technologies already help to browse through vast amounts of online publications (for example an RSS aggregator helps me to generate a daily literature survey; this can be further combined, for example here at Frienfeed, with other community-centered feeds; other aggregators highlight information by automatic clustering: Postgenomic and Scintilla). However, these tools remain imperfect and, in our reflection on the future of scientific publishing, we will need to find the right balance between the two strategies above and think of how the increasing efficiency of searching engines can be complemented by means providing continuous exposure to diversity.

|

| Posted: 18 Jul 2008 08:00 AM CDT Until yesterday, there was a span of about two weeks in which this blog laid dormant. I did that on purpose because I didn't want to give you all the blogging you crave. All three of you who may crave my blogging. And I'm guessing not one of those three even noticed the silence. Ah, the joys of insignificance. Besides being a lazy dick, I actually have a valid excuse for my silence: I was moving. Or, rather, I am moving (my move is not yet complete). Where am I moving? From grad-school to post-doc. It also happens to be a move from one city in the middle of nowhere to another city in the middle of nowhere. But I'm even more in the middle of nowhere in my new locale that I was previously. So much so, that when I looked out my window on the first day in my new home, this is what I saw:

And I think I saw at least one of those each day I was there. That's not to say that there aren't deers in the middle of nowhere town I lived in during grad school (there are plenty); but my new house is in the middle of nowhere within the middle of nowhere. It's isolate, which is not necessarily a bad thing. In closing, two things: First, hopefully blogging will resemble yesterday's activity more that the previous two weeks' worth. Second, it's not that I don't like living in the small towns (I do), it's just that I was surprised to be living so close to what can pass as "nature" in this modern age. I'm sure PZ Myers can top me by showing off how small his town is, how many woodland creatures he has prancing through his yard each day, and how many fucked up people he has sending him death threats every day. Read the comments on this post... |

| join the ACLU’s FISA lawsuit ! [biomarker-driven mental health 2.0] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 07:27 AM CDT Join with fellow citizens and the ACLU to stop warrantless government wiretapping … else, today your phone conversations and tomorrow (or, well, today, actually) your health records and genome. |

| Fair Use Rights [Sciencebase Science Blog] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 07:00 AM CDT

On the other hand, traditional publishers, database disseminators, and the commercial creative industry consider the investment they put into the creation and distribution of works as a basis for the right to charge readers and users and for profit-making. Meanwhile, adventurous organisations that are not necessarily beholden to shareholders, to other commercial concerns, and to learned society memberships, are experimenting with alternative business models with varying degrees of success. One aspect of copyright that arises repeatedly in any discussion is what is considered fair use and what kind of usage warrants a cease & desist order from the owner of copyright in their works. Now, Warren Chik, an Assistant Professor of Law at Singapore Management University, is calling for a reinvention of the general and flexible fair use doctrine through the simple powerful elevation of its legal status from a legal exception to that of a legal right. Writing in the International Journal of Private Law, 2008, 1, 157-210, Chik explains that it is the relatively recent emergence of information technology and its impact on the duplication and dissemination of creative works - whether it is a photograph, music file, digitised book, or other creative work - that has led to a strengthening of the copyright regime to the extent that it has introduced “a state of disequilibrium into the delicate equation of balance that underlies the international copyright regime”. Copyright holders have lobbied for their interests and sought legal extension to the protection over “their” creative works. But, the law in several countries has undergone a knee-jerk reaction that is not necessarily to the benefit of the actual creator of the copyright work or of the user. Chik summarises the impact this has had quite succinctly: The speedy, overzealous and untested manner in which the legal response has taken has resulted in overcompensation such that the interests of individuals and society have been compromised to an unacceptable degree. For some forms of creative works, such as music and videos, there has emerged a protectionist climate that has led to the creation of double protection in law the form of the digital rights management (DRM) system and anti-circumvention laws that allows copyright owners to prosecute those that attempt to get around such restrictive devices. This, Chik affirms, has “inadvertently caused the displacement of the important fair use exemptions that many consider the last bastion for the protection of civil rights to works.” Chik points out that this tightening of the laws run counter to the increasing penetration of electronic forms of storage and communication, the borderless nature of the Internet and the invention of enabling technologies such as the so-called “Web 2.0″. This in turn is apparently leading to a general social shift towards more open collaborative creativity, whether in the arts or the sciences, and what he describes as “the rise of a new global consciousness of sharing and participation across national, physical and jurisdictional borders.” Whether that view is strictly true or not is a different matter. At what scale will those who like to share a few snapshots among strangers or a small-scale collaboration between laboratories realise the need for a more robust approach to their images and data? For example, if you are sharing a few dozen photos you may not see any point in protecting them beyond a creative commons licence, but what happens when you realise you have tens of thousands of saleable photos in storage? Similarly, a nifty chemical reagent that saves a few minutes in a small laboratory each week could take on global significance if it turns out to be relevant to cropping a synthesis in the pharmaceutical industry. Who would Chik proposes not to destroy or even radically overhaul the present copyright regime, instead he endorses a no less significant reinvention of the general and flexible fair use doctrine through the simple powerful elevation of its legal status from a legal exception to that of a legal right, with all the benefits that a legal right entails. This change, he suggests could be widely and rapidly adopted. Currently, he says, fair use exists formally only as a defence to an action of copyright infringement. But, DRM and other copyright protection threaten this defence and skew the playing field once more in favour of copyright holders. “Fair use should exist in the law as something that one should be able to assert and be protected from being sued for doing,” Chik says. Such a change will render copyright law more accurately reflective of an electronically interconnected global society and also acknowledge the importance and benefits of enabling technologies and its role in human integration, progress and development. Chik, W. (2008). Better a sword than a shield: the case for statutory fair use right in place of a defence. International Journal of Private Law, 1(1/2), 157. DOI: 10.1504/IJPL.2008.019438 a |

| Around the Blogs [Bitesize Bio] Posted: 18 Jul 2008 05:02 AM CDT Here’s a list of blog posts worth passing along from the past couple of weeks, in the order I bookmarked them. The Costs and Benefits of the Latest, Greatest Cancer Drugs - What happens when the search for expensive cures crashes into fiscal reality?, and other musings. PLoS in Nature: The Big Picture - A record of news and opinion pieces in Nature on PLoS from 2001 to the present. Generation of Diversity, Phage Style - Simply amazing how protein diversity can be achieved. How Bacteria Recognize Kin - Brief comment on an interesting Science paper on bacterial recognition factors. |

| Trendspotting: Of micro-communities and software delivery [business|bytes|genes|molecules] Posted: 17 Jul 2008 11:27 PM CDT

We’ve also talked about NanoHub in the past. A press release on entitled Virtual world is sign of future for scientists, engineers reminded me that I had not visited the site for a while It is definitely one of the better designed sites of its kind out there, and looking at the site again and reading the press release got me thinking to a couple of themes that are no strangers to these pages (1) Is there a role for microcommunities in science? (2) Is the future of software delivery in science a virtual one? Lets talk about microcommunities first (given their small sizes perhaps they should be called nanocommunities or something). The community that I am peripherally involved with, The Biogang, is for all practical purposes a microcommunity of bioinformatics types. Similarly, Topsan is a community for structural biologists, EColiHub for people interested in E. Coli, etc. As a whole nanoHUB seems to be a portal for multiple microcommunities. In all cases there is a common thread that brings together people with interests that have enough overlap to be able to share some common goals and enough diversity to foster curiosity, conversation, and collaboration. nanoHUB also provides its users a virtual software environment. CARMEN fits that model as well. To some extent, so does myGrid, although it’s perhaps a little more complex, and I am beginning to see such examples more and more. In all cases, its not just about accessing one application, or even a metaserver for structure prediction, but a complete suite of services via the web. Over time, I see this form of delivery maturing further and even being used to access large scale simulations, doing data analysis from all kinds of experimental platforms, etc. As our internet pipes get fatter and the ability of scientists to develop scalable web resources improves, it is only inevitable. |

| Let's do some Reading on the Plausibility of Life [adaptivecomplexity's column] Posted: 17 Jul 2008 11:00 PM CDT I just got my hands on a recent book by two influential biologists, Marc Kirschner, chair of Harvard's recently created Systems Biology Department, and John Gerhart, a professor at UC Berkeley. |

| Positive Feedback Loops that Drive Cell Decisions [adaptivecomplexity's column] Posted: 17 Jul 2008 10:23 PM CDT Dividing is one of the trickiest things a cell has to do. The cell needs to faithfully copy its entire genome, with very few mistakes, and it needs to then divvy up those two genome copies equally among the two new cells that are created during division. Going through this process is a bit like going down a double black diamond ski run: once you set things in motion, there's no stopping until you get to the end. In the case of cell division, there are two critical points of no return: at the decision to start replicating DNA, and when it's time to equally split up the chromosomes. A cell that's going to copy its genetic material had better be ready, with all the necessary supplies in hand, because once the copying process initiates, it's a bad idea to stop: a cell can't really do much with a half-replicated genome, and it's in danger of permanently ruining its genome. And it doesn't do you any good to successfully finish that copying process, only to misallocate what you've copied among the two daughter cells. Without the right chromosomes in each cell, there is only a slim chance of survival. So how do cells make these critical decisions? |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The DNA Network To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email Delivery powered by FeedBurner |

| Inbox too full? | |

| If you prefer to unsubscribe via postal mail, write to: The DNA Network, c/o FeedBurner, 20 W Kinzie, 9th Floor, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

Intellectual property,

Intellectual property,

No comments:

Post a Comment